Are You Suited for an Immediate Annuity?

What retirees should know before buying.

Note: This article was originally published on Sept. 18, 2023. As today’s annuity rates are almost identical to those of that date, the article’s commentary remains fully relevant.

Narrowing the Field

The best way for retirees to increase their lifetime monthly payouts is to postpone receiving Social Security. The payoff from that strategy exceeds that of any reasonably safe alternative.

Some investors, however, want more. Among their choices are immediate annuities, which provide monthly payments for either the rest of the buyer’s life, or if structured as a joint-survivor benefit, for a couple’s lives. When purchased with a lump sum, such contracts are called single-premium immediate annuities, or SPIAs. (Note: There are many flavors of annuity, most of which are initially used for accumulating assets, not paying them. But those are a topic for another time.)

Case Study

Obtaining annuity quotes without interference is not easy; many websites that purport to provide the service are marketing tools, funneling the prospective customer’s data to an insurance broker. But there are a few places where consumers can browse. One is Blueprint Income, and another is Charles Schwab’s annuity calculator, which I used for this article. When asked the monthly payout on a $100,000 purchase made by (for example) a single 62-year-old male who lives in Illinois, Schwab’s software replies $606, providing a 7.27% payout rate.

Lifetime payments that exceed an annual 7%! Who would disagree? But that benefit requires context. First, annuity payouts include the investor’s capital as well as the insurer’s contribution. That 7.27% figure is therefore not a total return and may not be directly compared with investment performances.

Second, as this particular contract does not protect against the possibility of an early death, it manages a positive return only if the retiree survives long enough to spend the insurer’s money, rather than just his own. How long, exactly, is not intuitive. But we can arrive at a general sense of the contract’s virtues by using actuarial tables to evaluate potential outcomes.

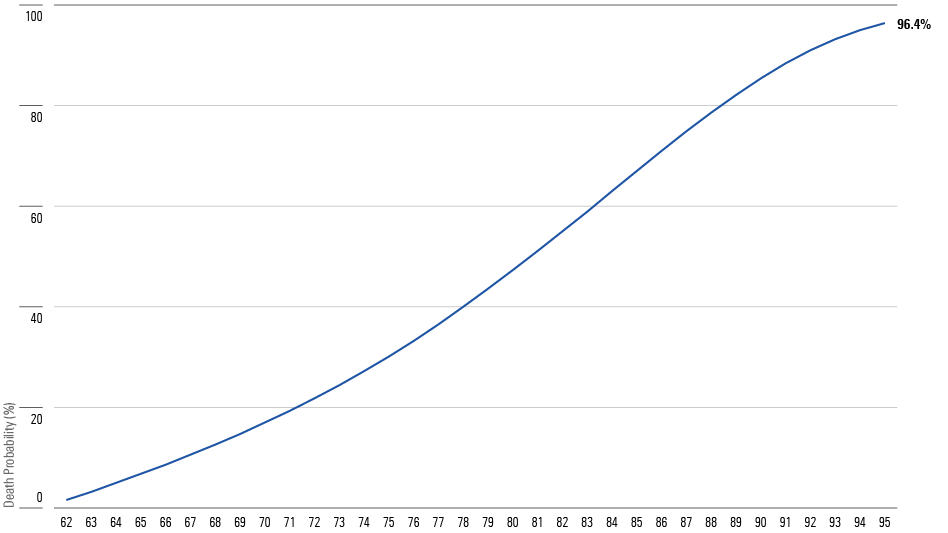

Social Security’s Projections

The following chart shows the cumulative probability of our hypothetical investor’s demise, per the Social Security Administration’s forecasts. There is a 1.6% chance that the retiree will die during the upcoming year. The probability reaches 25% shortly after his 73rd birthday, 50% when he turns 81, and 75% at age 87.

Cumulative Death Probability: Social Security's Estimates

The math makes our sample annuity distinctly unfavorable for shorter-lived buyers. Per Social Security’s projection, 25% of the time our retiree will expire within the next 11 years, at which time his $100,000 contract will have paid a maximum of $80,000. In such cases, as Georgie Best would have said, our retiree might as well have spent his cash sensibly on “booze, birds, and fast cars” rather than have squandered it.

Nor is the median outcome especially enticing. The back of an envelope reveals that the original capital will survive for 14 years, leaving only five years to be supplied by the insurer. No calculator is needed to appreciate the inadequacy of a $100,000 outlay that generates $138,191 over a 19-year period. Sure enough, Excel reveals that the internal rate of return for that situation is a modest 3.87%.

The Insurers’ Model

What gives? Surely competition would force insurers that sell such contracts to offer better terms, rather than a return that not only fails to match a Treasury bond’s for the median purchaser but is negative for one buyer in four.

The intuition is correct. In fact, our sample annuity is reasonably priced. The key consideration, as Morningstar’s annuity expert Spencer Look explains, is that retirees who buy immediate annuities tend to be much healthier than the norm. Consequently, the expected return on their purchase is substantially higher than the Social Security Administration’s forecast would indicate.

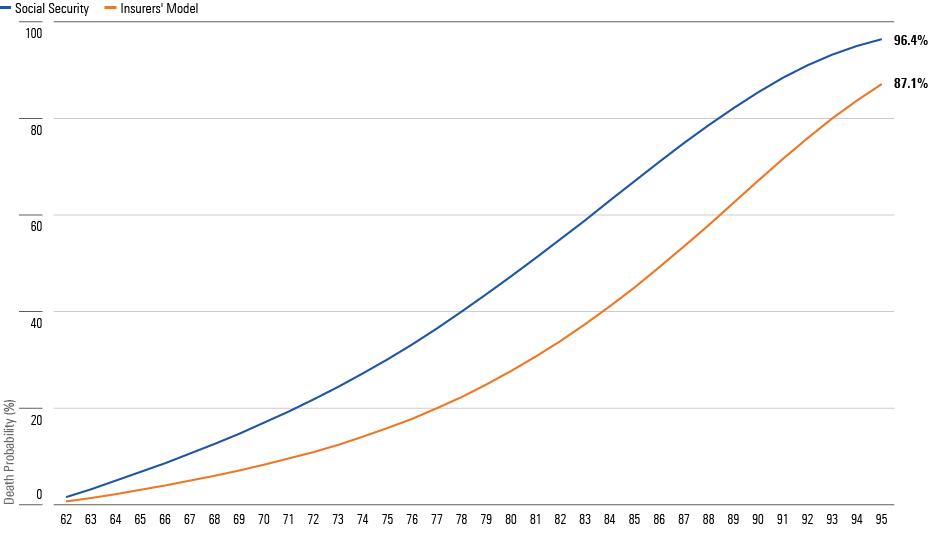

The chart below contrasts the life expectancies of immediate-annuity purchasers, as estimated by the standard insurance industry mortality table (each insurer uses different models, but this is a representative case), with those assumed by the Social Security Administration.

Cumulative Death Probability: Insurers' Model

Quite the difference! From the insurers’ perspective, the 25th cumulative death percentile will not arrive until age 79. The 50th percentile comes seven years later, and the 75th percentile not until the retiree turns 92. Under these conditions, the life annuity becomes a much better deal. The median buyer now receives an internal rate of return of 5.44%, which is well above what a Treasury bond would deliver.

Incorporating Cash Refunds

So far, so good. However, there remains one very large caveat. Although most retirees who match the insurers’ risk profile will prosper from buying SPIAs, an unlucky few will perform very poorly by dying before their principal has been exhausted. Happily, this drawback can be fixed through a cash-refund rider. Such provisions stipulate that if the annuitant dies before a specified date the contract’s unspent capital will pass on to his beneficiaries.

All things being equal, cash-refund features greatly enhance SPIAs’ appeal. Of course, you would expect that all things would not be equal, because insurers would sharply reduce the SPIA’s payout to cover the benefit’s cost. Think again. (I certainly did.) According to Schwab’s calculator, the yield reduction for adding a 10-year cash-refund rider to our sample contract is almost nonexistent. Doing so cuts the annuity’s monthly payout from $606 to $595, thereby lowering the annual percentage from 7.27% to 7.14%. That’s barely worth noticing.

Effectively, the 10-year cash-refund rider supplies the closest thing that one can find to a free investment lunch. My former colleague David Blanchett, who now heads retirement research at the asset-management firm PGIM, explains why: The actuaries who work for insurers know that clients who care about cash-refund provisions are likelier to have health concerns. Consequently, they price such contracts more aggressively.

Conclusion

The upshot is simple. For most investors, the expected return on immediate annuities is relatively low, because those contracts are priced for (and typically bought by) unusually healthy customers. In some cases, such annuities may nonetheless be sensible choices, because they are, after all, insurance. Not all insurance contracts need to be “profitable” to fulfill their purpose.

That said, SPIAs clearly make the most sense for those who have reason to believe, owing to both genetics and lifestyle, that they will enjoy longer-than-average life spans. They will likely be better yet when accompanied by cash-refund provisions. In most cases, such riders cost considerably less than the benefit that they supply.

How to Not Outlive Your Money

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)