Fractional Real Estate Ownership: Trick or REIT?

Democratizing real estate is an intriguing concept, but some jump scares lurk in the fine print.

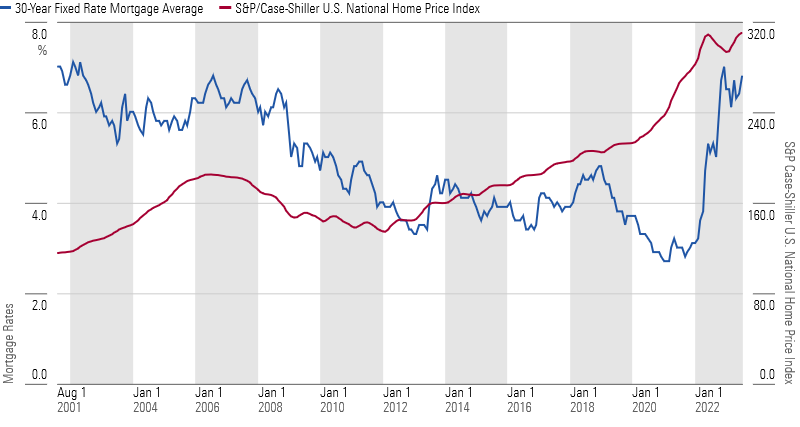

With mortgage rates well past 6% and housing prices across the country broadly holding firm through July 2023, investing directly in real estate has spiraled out of reach for many.

Home Prices and Mortgage Rates, 2001-23

A new tool promises to help fill the gap: fractional real estate investing, which confers partial ownership of a single property. There’s no standard definition for what fractional ownership entails. Some businesses that bill themselves as fractional real estate platforms offer access to a property on a partial basis, like a timeshare would. What we’re looking at here is different: services where investors put up a certain amount of money—as low as $50 in some cases—and in exchange they receive a portion of the rental income from a particular property, as well as any capital gains if that property appreciates.

The idea may sound very similar to fractional shares, which allow investors to buy less than one full unit of a stock or exchange-traded fund. But it’s not, because every piece of real estate is unique, which means that the shares that get created are less liquid than fractional shares of stocks and ETFs generally are. Investing in less liquid securities may have some behavioral benefits, but it also courts substantial risk during market stress. In this instance, I’m not sure that risk is necessary—because investors have a much more proven way to get real estate exposure, right under their noses.

Background on Fractional Real Estate Investment

The companies offering fractional real estate investments are generally not brokerages like Robinhood or Schwab. They’re startups: Lofty AI was founded in 2018, Arrived in 2019, and Here in 2021. There are at least six more in the United States, and other similar firms in Canada, that all offer roughly the same services. (For the purposes of this article, I’ve limited my analysis to these three. They permit nonaccredited investors to invest and have similar overlapping goals of seeking rental income from residential or vacation properties.)

Today, the market is still small. Investors on Arrived own fractional interests in real estate worth $119 million as of October 2023, while investors through Here own properties collectively worth roughly $10 million. On average, investors have made fairly cautious allocations. For Arrived, I sampled 10 properties, and the average investor fronted $400. According to a review of all of Here’s properties, the average investor put up around $710 as of October 2023.

Reinventing the Wheel?

To my eyes, fractional real estate investing looks very similar to investing in a REIT, or a real estate investment trust. In fact, a few fractional real estate platforms actually structure some of their investments as a specific type of REIT, known as a public nontraded REIT.

What’s the same:

- Both securities require a smaller upfront investment than a traditional down payment.

- Neither security entails day-to-day property management responsibilities like the ones a traditional landlord would have.

- Tax treatment is broadly comparable.

- In both cases, the investor doesn’t get the right to occupy the property, even on a partial basis.

Now, there are some crucial differences to keep in mind as well.

- A REIT typically diversifies across multiple properties. Fractional ownership applies to one specific underlying property. That means an investor purchasing fractional real estate can select the individual property they want to invest in from among the ones that the platform has identified, whereas a REIT investor gets exposure to all the properties the REIT owns.

- REITs can be publicly traded, while fractional real estate investments generally are not.

- Fractional real estate could offer higher yields than a traditional REIT.

Smaller Bites, Still Hard to Chew

The key differences from a REIT arguably make fractional real estate investing a worse experience for investors, at least today.

1. A REIT typically diversifies across multiple properties. Fractional ownership applies to one specific underlying property.

For some, the ability to pick and choose different securities is one of the most satisfying parts of investing. This is especially true in real estate, where property characteristics are highly idiosyncratic and location is paramount.

But with fractional real estate platforms, investors get less choice than they might expect. For example, Lofty AI has fewer than 150 properties as of October 2023, and only one is currently accepting new investors. (The rest have to purchase an existing share on the secondary market.) Here has 13, none of which are accepting new investors. Although it varies, Arrived surfaces roughly 13 properties each month. These platforms generally have some geographic constraints, too. All three operate in fewer than 20 states.

2. Although there are notable exceptions, most REITs are publicly traded, while fractional real estate investments generally are not.

Arrived’s typical holding period lasts at least five years, during which time investors generally are not permitted to liquidate their investment. Lofty AI allows investors to sell their shares but only to other users of the platform, and fees of roughly 2.5% are attached. Here has an investment horizon of 10–15 years and “does not offer investors individual liquidity for their property shares during our investment period.” Spooky.

3. Potentially higher dividend yield than a traditional REIT.

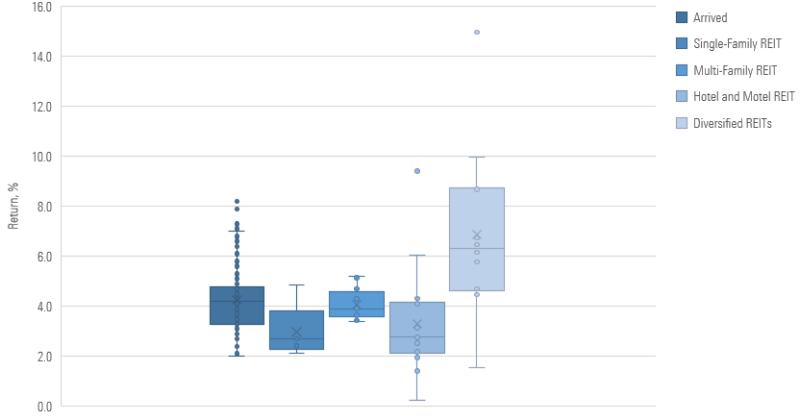

Property type is an important consideration here. In general, vacation rental property yields tend to be more variable because they have shorter-term agreements relative to single-family and multifamily residential properties. It appears that, in general, Arrived’s properties have delivered a higher average rental income than your typical single-family REIT’s dividend yield over the past year through October 2023, but that’s inclusive of some vacation properties, and the median is not meaningfully higher than a diversified multifamily REIT.

Arrived Annualized Rental Income vs. TTM Dividend Yield From U.S. REIT Industries

It’s also important to keep in mind that all of these figures capture performance over 12 months—too short of a time horizon to conclusively determine one way or another whether the hypothetically higher yields hold true in practice.

Other Things That Go Bump in the Night

These platforms are new, which means that regulation is not fully settled in cases where the platform bypasses existing security structures like public nontraded REITs. If things go awry, there’s no guarantee that the road to recourse is going to be clearly marked.

Costs are another factor. These platforms charge a mix of commissions, asset-based expense ratios, and transaction costs, all of which may dim the appeal relative to a traditional REIT where all property management costs are baked into the operating results and the investor does not have to pay extra out of pocket.

Some investors may want a little exposure to a single piece of property and don’t want the hassle of being a landlord—these platforms are poised to help them do it. But investors might want to think long and hard about whether it’s necessary to meet their investment goals when REITs get the job done just fine.

The views expressed here are the author’s.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BL6WGG72URAJJJCPC4376SZKX4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)