A New Type of Fund Promises Access to Private Markets … at a Price

This vehicle sits at the nexus of two colliding trends in investing.

Private markets and public investors continue to collide in new and interesting ways. Interval funds allow individual investors to commit their capital to strategies that invest directly in private markets. Listed private equity exchange-traded funds invest in the publicly traded shares of firms that offer private-market strategies.

These types of strategies have ridden the wave of increased appetite for nontraditional investments. Thanks to the booming private wealth management industry, high-net-worth investors can demand access to investment managers that once only answered the calls of pension funds and sovereign wealth. But a key hurdle remains: How are these investors supposed to get access to and manage the capital commitments required of private capital?

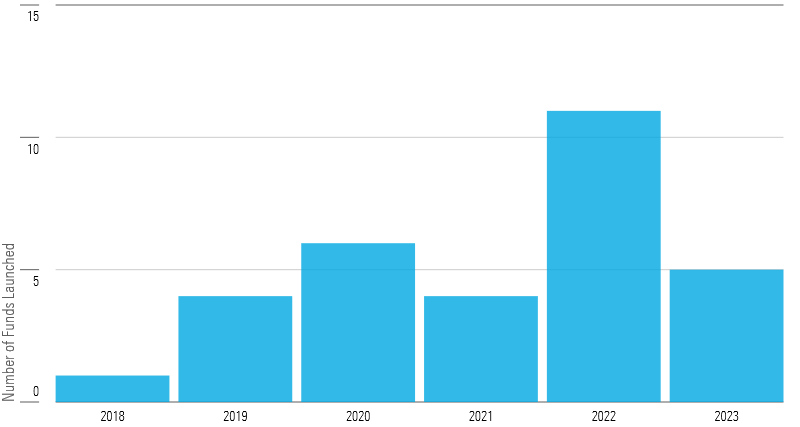

Enter private-market funds. These funds go by different names but most feature some combination of terms like “private market,” “access,” and “opportunity.” These types of funds had a banner year in 2022 with 11 product launches. This year is on track to match it.

Private-Market Access Fund Launches in 2023 Are on Track to Match Those in 2022

More and more frequently, filings are coming from brand-name firms, including the Carlyle Group and J.P. Morgan in 2022 and Apollo throwing its name into the ring in 2023.

What Are Private-Market Funds?

Private-market funds, or private-market access funds, are closed-end funds that offer exposure to private assets, often private equity, by investing in other third-party managed funds that, in turn, allocate to private firms. Sometimes a private-market access fund may directly invest in private companies as well.

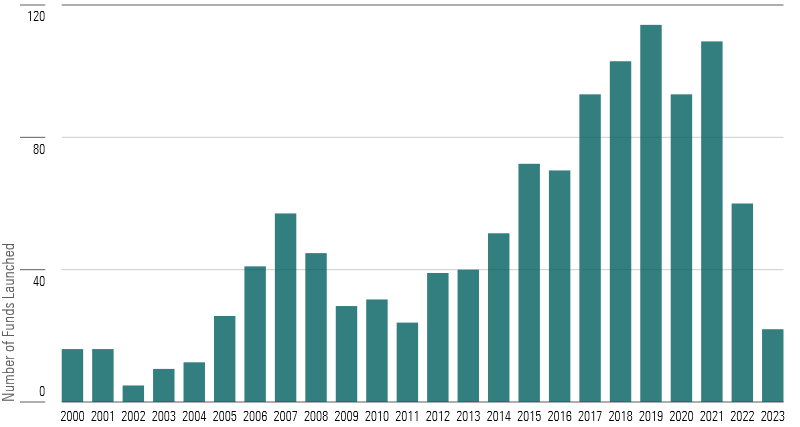

Although the closed-end vehicle puts a modern twist on it, the concept is not a new one. Private equity funds of funds utilizing a general partner/limited partner structure have been around since at least the 1970s, although they didn’t catch on until the 1990s.

Since 2000, Interest in Private-Market Funds of Funds Has Grown

The concept was last in fashion during the late 2000s among institutional investors that wanted access to private investments but lacked the analytical resources to construct a portfolio themselves. Today the strategy is experiencing a new life as the favored vehicle for high-net-worth individuals.

The Pros

The biggest benefit of these funds is access. Depending on the size of their portfolio, high-net-worth individuals may not be able to access private markets in another vehicle.

For investors who can, what makes these closed-end funds different from other private-market strategies is that private-market funds don’t have to return principal to investors. Instead, the investment can live on perpetually, like a typical mutual fund would. Some, though not all, come in an interval fund format that allows for periodic redemption. Vehicles that have a perpetual life can develop a performance track record that’s more directly comparable to other asset classes.

In addition, investors can outsource the due-diligence process to firms with far more experience and scale. They might get access to managers that otherwise have prohibitively high minimum investments. Funds of funds also allow investors with less capital to efficiently diversify across various types of private-market strategies.

The Cons

Private-market access funds often don’t have a full portfolio already assembled when they first go live. Thus, early investors might not know which private equity managers they might ultimately get access to.

While private-market access funds can be more liquid and simpler to use than traditional private-market funds, they’re also costly. Funds of funds pile another layer of fees on top of the typical 2% management fee/20% performance fee that most private equity managers charge. Generally, those extra fees fall in the neighborhood of 1% management/10% performance. All in, effective expense ratios can run 3.5% or more—even with waivers.

Finally, some of these funds have commitment periods, which means that investors’ capital is locked up for a preset window. If they attempt to withdraw, there are extra penalty fees layered on top. Then there are also fund-level withdrawal limits. If those are breached, investors may not be able to get access to their capital at all.

Clash of the Titans

The private fund-of-funds market is still relatively small compared with traditional private equity and other quarterly redemption vehicles that focus on direct private investment opportunities.

What’s changing now is that traditional asset managers are getting into the game. For example, Vanguard announced a partnership in February 2020 with HarbourVest, a private equity fund-of-funds manager. (Importantly, that partnership utilizes the GP/LP structure rather than a closed-end fund.)

BlackRock responded with its first closed-end fund in June 2020, and Neuberger Berman followed suit with a closed-end counterpart to its long-running Crossroads suite. Other firms like MassMutual have also filed for private-market funds but have not yet launched a live investable vehicle.

Private-Market Funds Launched By Public-Market Firms

It’s not just public-market firms that are trying to expand their reach in the private markets. There’s also interest from incumbents in the alternative asset-management space looking to expand their client base into private wealth.

Private-Market Funds Launched By Private-Market Firms

Are Private-Market Access Funds the Investment of the Future?

While we’re certainly seeing more interest in private markets from individual investors and the fund industry, it doesn’t seem likely that private-market access funds will go mainstream given the cost, complexity, and illiquidity involved. There are other ways besides a fund-of-funds structure to alleviate some of the challenges of private markets, such as interval funds that invest primarily in private markets themselves or purchasing existing private-equity fund stakes in the secondary market.

Still, the mutual fund giants have a fairly strong track record of simplifying complex—bordering on herculean—investment decisions. And the alternative asset managers have decades of experience at their disposal, experience that is impossible to substitute. Given that private-market access funds sit at the crossroads of these two behemoths, it could be worth examining whether that access is as beneficial in practice as these firms believe it could be in theory.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BL6WGG72URAJJJCPC4376SZKX4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)