Should Your Retirement Withdrawals Mirror RMDs?

Like all variable strategies, a required minimum distribution system entails trade-offs.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article was published on May 2, 2023.

This method is inherently “safe” and ensures that a retiree will never deplete the portfolio, because the withdrawal amount is always a percentage of the remaining balance. Basing portfolio withdrawals on RMDs also helps ensure that retirees wring the most from their portfolios that they possibly can, a benefit that was on full display in our research on safe withdrawal rates. The lifetime withdrawal rate—an internal-rate-of-return-type calculation that measures a retiree’s lifetime payout from a given withdrawal strategy—was higher with an RMD-type system than any other. A retiree using RMDs to determine annual withdrawals would enjoy a lifetime withdrawal rate of 5.4%, whereas most of the other approaches we tested delivered lifetime withdrawal rates of 4.0% or less.

Yet like all variable strategies, an RMD system entails trade-offs—notably, very volatile cash flows from year to year as well as the lowest residual balance amount at year 30 of any strategy we tested. As such, it’s best suited for a very specific type of retiree—ideally, a wealthier retiree with substantial nonportfolio income sources (to help buffer the annual cash flow volatility from the portfolio) and without a big bequest motive.

Why It Works

While some of the flexible spending strategies can get complicated, an RMD-type system is anything but. A retiree need only find two factors each year—portfolio balance and life expectancy—to guide how much to take out.

Even more important, an RMD system is efficient, limiting a retiree’s spending in bad years and underspending in good ones. Bringing life expectancy into the mix further adds to the efficiency of an RMD-style system. Initial withdrawal rates are fairly modest, which helps ensure that the portfolio lasts over a possible 25 or 30 years. Relatively low initial withdrawals also help safeguard against sequence risk—the prospect of encountering a down market early in retirement. Not only is the retiree automatically spending less because the balance is down in such an instance, but the allowable percentage is also lower because early withdrawal percentages are lower. As life expectancy declines with age and anticipated lifetime portfolio demands diminish, the portfolio divisor gets smaller, enabling the retiree to spend a higher percentage. (Of course, that’s the opposite of actual retiree spending patterns: higher early on, lower later in life.)

Before we go any further, it’s important to note that there are multiple ways to calculate life expectancy and, in turn, determine RMDs. The most common way to calculate RMDs—and the version used by most people taking distributions from IRAs or other retirement accounts—is by using the IRS’ Uniform Lifetime Table. That table builds in conservative assumptions about life expectancy and deters overspending by adding another 10 years to the account owner’s life expectancy. There’s an additional table, theJoint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table, that’s geared toward account owners with spouses who are at least 10 years younger; life expectancies on it are more generous still, leading to even lower withdrawal percentages. For our research, we employed the IRS’ Single Life Expectancy Table, which incorporates life expectancy for a single individual. As such, it assumes a shorter life expectancy and guides higher spending rates than is the case with the two aforementioned tables. Retirees who wish to be more conservative should consider the Uniform Lifetime Table.

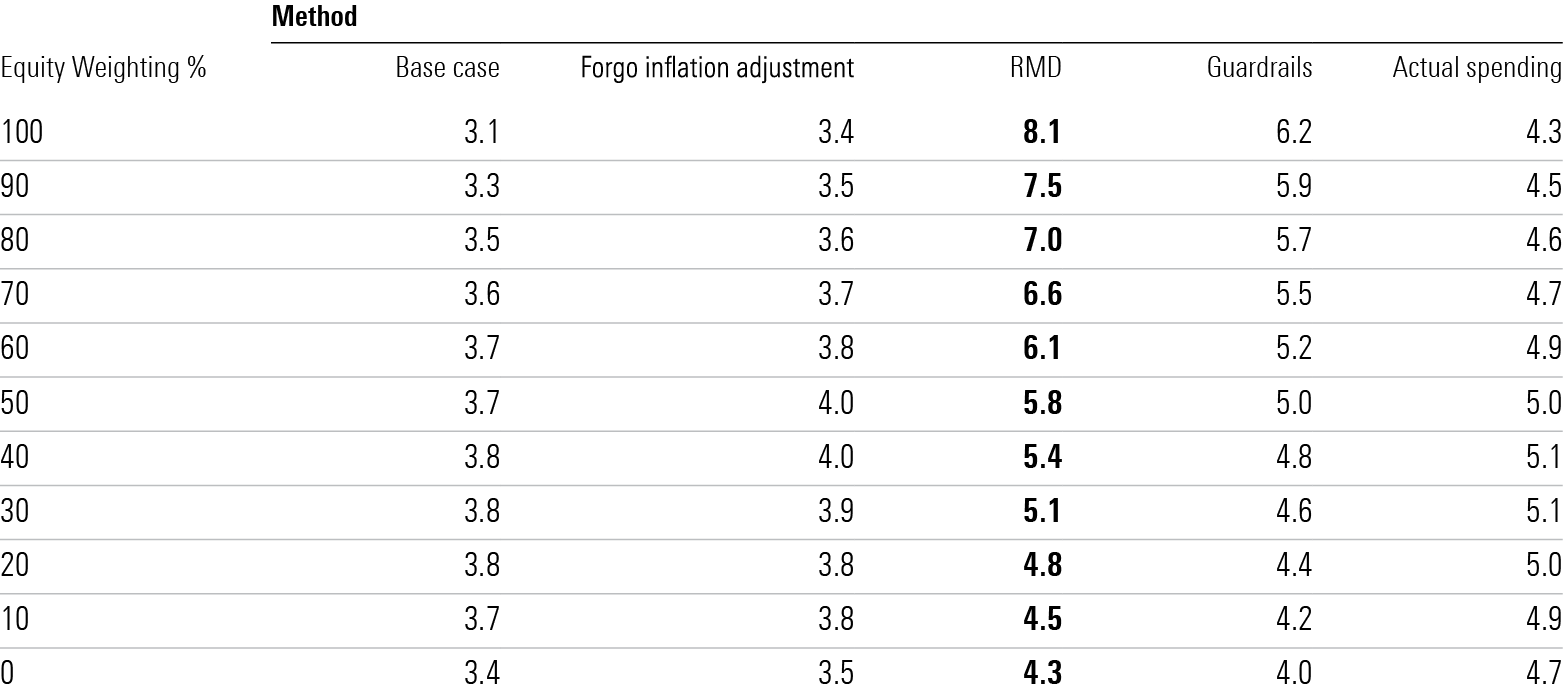

Lifetime Withdrawal % by Withdrawal Method and Asset Allocation

The table above shows the benefits of an RMD-type system for lifetime withdrawal rates. While lifetime withdrawals from an RMD-type system are higher than any other system across every asset-allocation mix, they’re especially lofty for portfolios with high equity allocations. (This article discusses the other withdrawal systems that appear in this table.) That is because the portfolios with higher equity allocations provided larger “raises” in annual withdrawals following good years, thereby enlarging lifetime withdrawal amounts.

The Catch(es)

There are a few downsides to using RMDs to guide portfolio withdrawals, however. The biggest one is that RMD-focused retirees have to endure significant variations in their annual spending. That stands in contrast with the system of fixed real withdrawals that we used as the base case in our research. Our base-case fixed-real withdrawal system, while delivering lower starting and lifetime withdrawals than dynamic methods like RMDs, ignores portfolio fluctuations in favor of giving retirees a steady, paycheck-equivalent stream of cash flows that’s adjusted for inflation. The exhibit below illustrates the extreme cash flow volatility of the RMD approach relative to all of the other systems we tested.

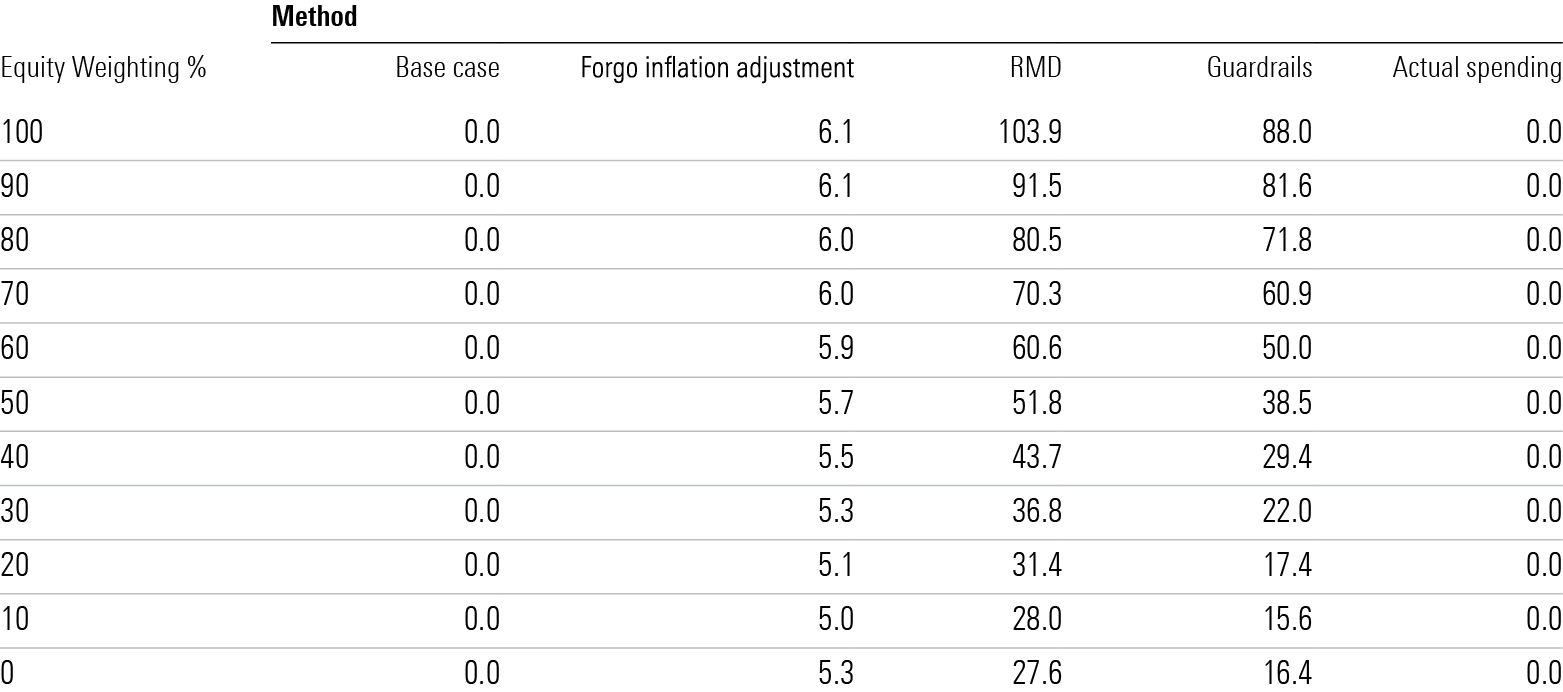

Year 30 Cash Flow Standard Deviation by Withdrawal Method and Asset Allocation

The past few years provide an excellent example of cash flow volatility in action. A 65-year-old retiring in 2022 with a $1 million balanced stock/bond portfolio could have taken out $33,000 in 2022, based on the 3.3% initial withdrawal rate that we pointed to in our research at year-end 2021. For 2023, her withdrawal amount would have been $35,310—her initial withdrawal plus an additional 7% to help her spending keep pace with inflation. In other words, her withdrawal would ignore changes in her portfolio’s value and instead aim to hold steady, on an inflation-adjusted basis, from one year to the next.

By contrast, a 65-year-old retiring in 2022 using the RMD method to guide withdrawals from the same $1 million balanced portfolio would have taken $43,668, or 4.37% of her balance, in 2022, as dictated by the IRS’ 2022 Single Life Expectancy Table. She’d calculate her 2023 spending based on her new life expectancy and her portfolio balance at year-end 2022. Her portfolio balance would have dropped to $794,712 (including her year-one withdrawal plus the portfolio’s 2022 losses), so her 2023 payday is $36,123. That’s still higher than the $35,000 and change that the fixed-real withdrawal system would have afforded, but it’s more than $7,000 less than she received in 2022.

Of course, ratcheting down withdrawals when the portfolio value is down helps protect the RMD retiree from overspending in weak market environments. Moreover, she’d get to take a raise when her portfolio has gains, and that, along with the growing withdrawals as life expectancy declines, explains how an RMD-based system is able to deliver high lifetime withdrawal rates.

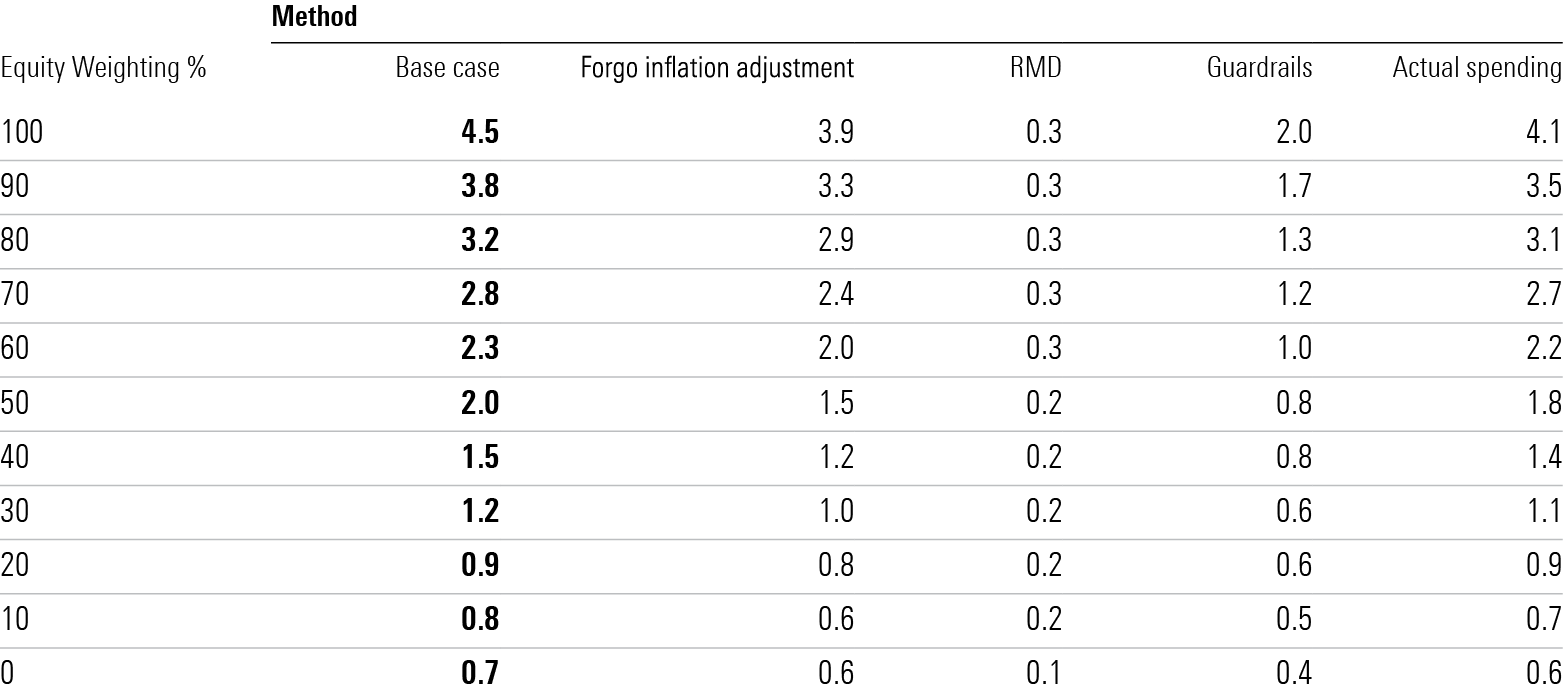

Median Ending Value Year 30 ($ Mil) by Withdrawal Method and Asset Allocation

Another major caveat associated with the RMD method is that it tends to leave lower residual balances after a 30-year period, and that’s by design. Updating each year’s withdrawal to factor in the portfolio balance and the current life expectancy means that the withdrawal amount is frequently ratcheting up, encouraging the retiree to enjoy the fruits of good portfolio performance. Meanwhile, systems that don’t factor in portfolio performance or age but instead adjust only for inflation don’t give the retiree any “credit”—in the form of increased paychecks—for the portfolio performance. As a result, the asset pool is typically much larger at the end of a 30-year period than is the case with dynamic systems such as RMD-based withdrawals. That’s a key consideration for bequest-minded older adults, though it’s worth noting that an RMD system lends itself well to lifetime giving. In years when a retiree has an overage that exceeds their spending needs, those extra funds can be deployed to family or charity.

Conclusions

In the end, using RMDs to guide withdrawals will be a good fit for a very specific type of retiree. Because of the higher lifetime payouts and lower average ending balances, it’s best suited to retirees who are more focused on maximizing their own consumption during their lifetimes, including lifetime gifts to charity and family, than leaving a big bequest. The volatility of RMD-based cash flows, however, also means that the approach is most appropriate for wealthier retirees who have a bigger share of their budgets going to discretionary spending than less wealthy retirees; those expenses are easier to adjust than daily fixed expenses. In a similar vein, the cash flow volatility of an RMD approach makes it most appropriate for retirees who are receiving a significant share of their spending needs—especially their fixed spending needs—from nonportfolio sources of income like Social Security or a pension.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/06-25-2024/t_f8ae5dc770f14b3d8f21379e20cb1857_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)