A Tax-Aware Alternative to Cash

Exploring box spreads and their potential use cases.

Houston, we have liftoff. Treasury bill and other fixed-income yields soared past 5% in April 2023 and have stayed there, with the 1-year Treasury bill reaching 5.4% by September. This has sparked a search for ways to improve on the paltry interest rates many investors experience in savings and sweep accounts.

High-yield savings accounts, money market funds, certificates of deposit, and Treasury bills all serve as compelling higher-yielding alternatives to traditional savings and sweep accounts. But all of these strategies share one thing in common: For federal tax purposes, interest payments qualify as investment income. Investment income is taxed at the same rate as a person’s ordinary income, and it contributes to an investor’s top marginal tax rate.

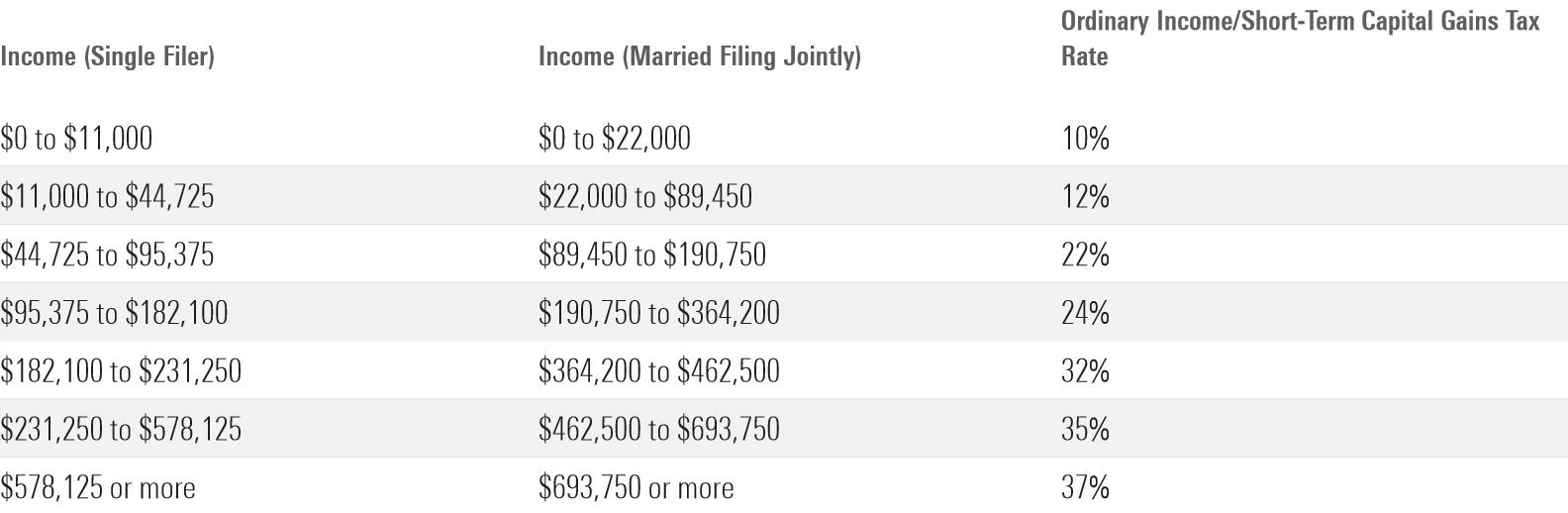

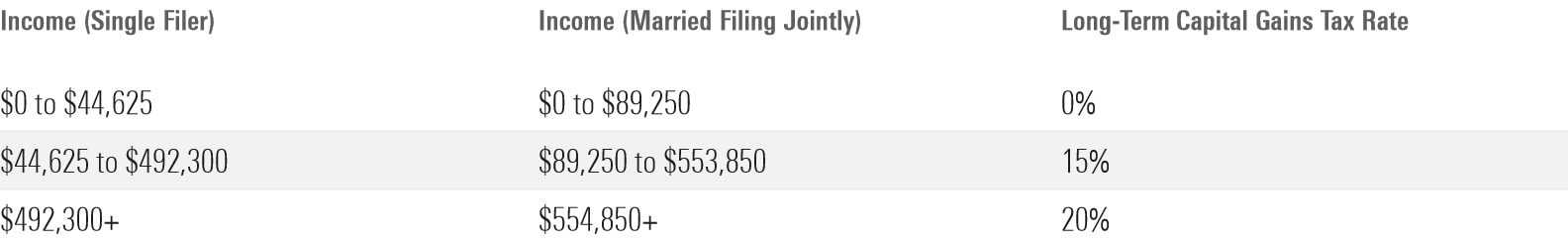

With tax rates between 10% and 35%, ordinary income is arguably the least-favorable tax treatment an investment return can have. But because interest rates were so low for so long, it hardly mattered, as most investors earned precious little on their cash. As yields rise, though, the tax treatment of cash-like instruments for tax purposes becomes more crucial.

As the old saying goes: Necessity is the mother of invention.

There is another way to invest at short-term Treasury bill rates that’s been used in institutional Treasury management for years, called a box spread. With higher interest rates and higher potential tax liabilities, the idea now has attracted attention beyond its traditional user base.

What Is a Box Spread?

Box spreads seek to extract the implied one-year Treasury bill yield by investing in options. In theory, the investment strategy should offer similar gross returns to Treasury bills, albeit with slightly higher risk. By stripping out this embedded rate instead of receiving it as an explicit interest payment, there is a key benefit—some returns may qualify as a capital gain instead of ordinary income.

At best it’s only a partial benefit. The most popular options tend to be taxed at a blended rate of 40% short-term and 60% long-term capital gains. Short-term capital gains are taxed at the same rate as ordinary income, somewhere between 10% and 37%.

Ordinary Income Tax Rates by Tax Bracket and Filing Status, 2023

Long-term capital gains tax for investors follows a different schedule, and ranges between 0% and 20%.

Capital Gains Tax Brackets by Income and Filing Status, 2023

An investor taking returns in the form of capital gains may not necessarily receive a lower tax bill overall. Every individual’s tax situation is unique, and Treasury bills and some funds that invest in them are not subject to state income tax, which may be a crucial benefit. But for an investor in the 32% tax bracket with a $100,000 portfolio earning a 5.6% yield, a box spread options strategy could deliver federal tax savings of up to $510 a year over a comparable strategy that pays out its returns as investment income. (This analysis presumes all of their gains qualify for the 60% reduced rate.) In percentage terms, that translates to savings of 0.51%. It may seem like a small amount, but it could add up over time.

How Does it Work?

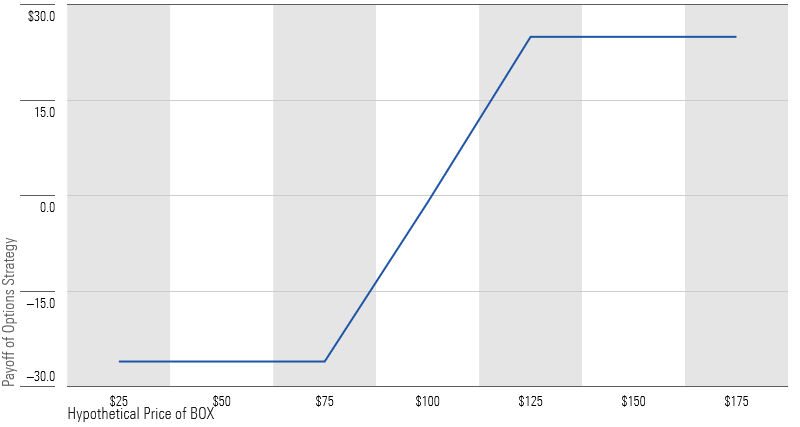

Wesley Gray of Alpha Architect has already explained this principle exceptionally well, but I’ll take a stab at it. A box spread consists of two types of options contracts: a call and a put. To set one up properly, an investor takes two opposing positions in each contract for a total of four contracts. The first position is called a bull spread. To keep the math simple, let’s assume that the options are written on a hypothetical company called BOX, which is trading at $100 a share. The cost to purchase a call is $35, and the cost to sell a call is $9.50, for a net premium of $25.50.

Bull Call Spread Positions

When an investor blends two calls in different directions—a call that they’ve bought and a call that they’ve sold—it creates a payoff profile that profits when an investment goes up a little but not a lot.

Payoff Profile of a Bull Call Spread

Let’s assume for simplicity’s sake that buying a put costs $30, and selling a put costs $8 for a net outlay of $22.

Bear Put Spread Positions

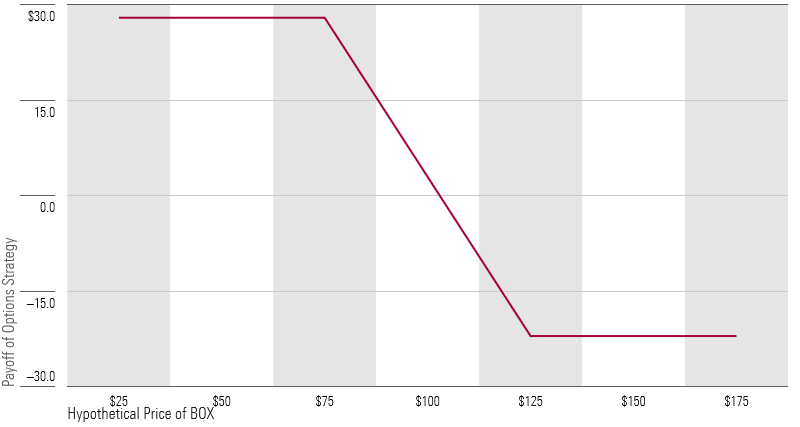

Buying a put and selling a put yields the mirror image of the graph above—a strategy that benefits when a stock goes down a little but not a lot.

Payoff Profile of a Bear Put Spread

Combining the two positions leaves you with zero exposure. The two positions cancel each other out—sort of.

You’ll note that the strike prices are slightly different, which creates the box. $125-$75 = $50. $50 is the implied payoff of the trade. No matter where the market goes, that’s the amount that the trade is structured to return to the investor at settlement.

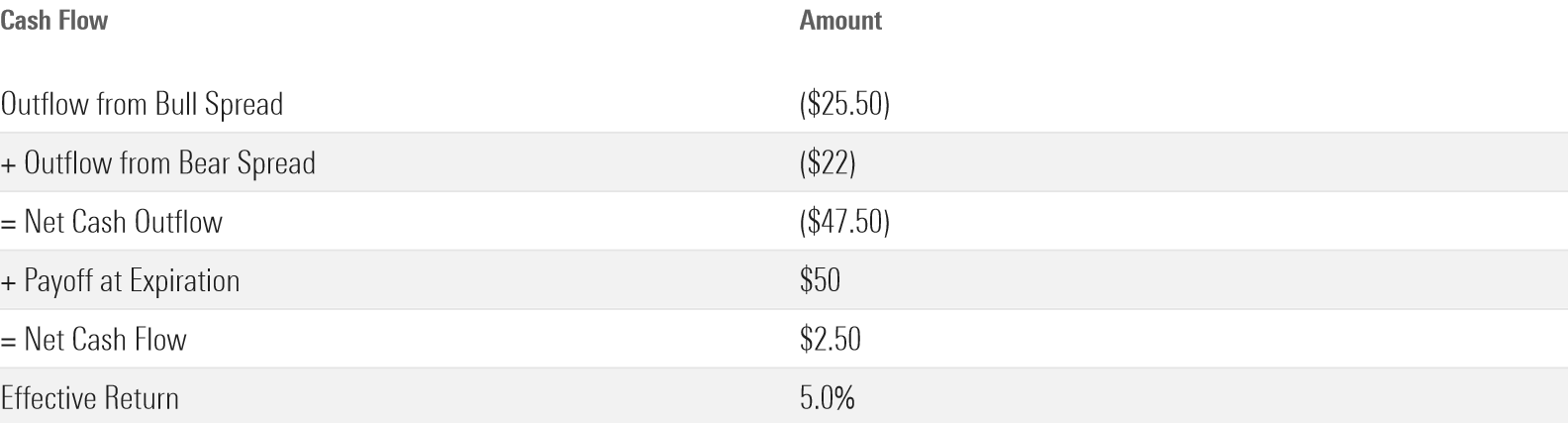

Of course, in investing there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Options contracts cost money to own. Because of the way this trade is set up, the value of the options sold is always going to be lower than the value of the options purchased. In essence, you have to make an initial investment upfront for the effective guarantee of receiving that $50 later on down the line.

Hang on—putting money down upfront in exchange for expected future cash flows? That kind of sounds like a bond.

Academic research bears this theory out. By virtue of a principle known as “box-spread parity,” the total amount of money an investor has to spend in premiums upfront to construct a box spread is equal to the gap between the strike prices, discounted back at the risk-free rate.

Cash Outlays from a Box Spread

I’m Not Actually Supposed to Set One of These Things Up Myself, Am I?

Probably not. There’s the initial operational hurdle, which requires an investment of time and effort, and forces you to live with the certainty that you cannot touch your savings for a year. (The options that this trade is built on are called European options, and you can only exercise them once at the expiration of the option.)

There’s also the catch is that the yields on a box spread are actually higher historically than the yields on a Treasury bill. That should put investors on watch: Higher yields often indicate that there is some implicit risk or inconvenience, otherwise that advantage would be arbitraged away. There are many potential explanations for the gap, including the drag of transaction costs or counterparty risks.

There is a potential solution on the horizon: exchange-traded funds that construct the box spread on investors’ behalf, at least one of which has just gone to market in the past year. That said, these strategies are still fairly unproven. It remains unclear whether the ETF vehicle can pass the full tax benefits of a box spread through to investors. Plus, the Treasury bill rate will fluctuate over time, but the ETF charges fees regardless, opening up the possibility of a negative real return if yields fall below the stated expense ratio. We’re still a few years out from knowing whether this will work in practice.

More to the point, although box spreads stand a good chance of delivering cash-like returns, they’re not a cash-like instrument. Treasury bills, certificates of deposit, and high-yield savings accounts are explicitly backed. Municipal money market funds are tax-free at the federal level, may qualify for additional state income tax exemptions, and feature an FDIC guarantee, too. No matter how tempting higher yields may seem, options and ETF returns do not.

5 Ways to Be a More Tax-Savvy Investor in 2024

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NSVUOQPZGJF7LCEGN76XGJKQII.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/Q7IH7AVNNZEQ3ALFR77S3T5V7I.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)