When Low Risk Means High Risk

Investment caution can be dangerous, too.

Treasury Bill Rivals

In total, 169 mutual funds and exchange-traded funds registered in the US officially list a Treasury bill index as their prospectus benchmark. That selection is indefensible. Every investment has a higher expected return than Treasury bills because every investment is riskier. Thus, the test is rigged. (Insert election joke of your choice.)

Those 169 funds are a strange assortment. One might expect funds claiming to compete with Treasury bills to exercise a few specific strategies, such as ultrashort bond or equity market-neutral. However, they occupy 20 distinct fund categories. The only commonality is that all are marketed as conservative investments.

Well, to be honest, they share a second similarity: None has performed especially well in recent years. Over the past decade, only six funds among that large group have exceeded a 5% annualized return. Even that result deserves an asterisk, however, because those funds did not behave like their benchmarks. The steadiest relative winner, LoCorr Long/Short Commodity Strategy LCSIX, matched the volatility of a 40% stock/60% bond portfolio. That’s not akin to a Treasury bill.

The Indexed Approach

Par for the course, I decided. All are active funds, carrying expense ratios that average above 1% (a hefty sum when a Treasury bill is the comparison!). Most also use complex strategies. Shareholders do well by avoiding funds that attempt to overcome their cost handicaps by resorting to investment trickery.

One should seek instead a low-cost portfolio built from the everyday investments of stocks, bonds, and cash. However, when I tried to devise asset allocations that would have done so over the past 10 or 15 years, while also offering low volatility, I was unsuccessful. True, I could beat almost all the funds benchmarked against Treasury bills by investing solely within the US. But not by much. Also, such an assumption was ahistoric. Conventional investment wisdom, both then and today, is that investors should diversify their holdings internationally.

In summary, no investment path appeared to work. Real-world funds employing such diverse tactics as long-short equity, macroeconomic trading, owning multiple alternatives strategies, and event-driven equity were all unable to combine healthy returns with relative stability. My index fund creations weren’t much better.

No Escape

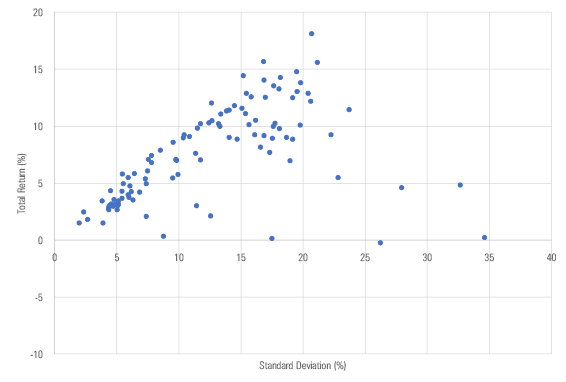

I tested that hypothesis by looking at the trailing 15-year return for all fund categories, hoping to find exceptions to the rule. The y-axis of the following chart plots the average annualized returns for every Morningstar Category that existed during that period. The x-axis depicts their standard deviations. If risk and returns have been directly related, the dots would plot a straight line running from bottom left (lowest return, lowest risk) to top right (highest return, highest risk).

No Risk, No Return

There was no refuge. Not a single fund category managed to break the general pattern. To be sure, many fell short. That lamentable dot at the bottom right of the chart represents gold funds (“specialty precious metals” as Morningstar officially calls them), which delivered a 0.25% annual gain along with a near 35% standard deviation. Other duds included Chinese, Latin American, and energy stocks. There were plenty of flops, but no surprise winners.

Regrettably, that picture flattered. For investors, nominal returns are beside the point. What matters is the after-inflation performance of their assets. Since the annualized change in the Consumer Price Index from April 2009 through March 2024 was 2.60%, that means that any fund category that earned a nominal return below that amount lost money for its shareholders, when calculated in real terms.

Twelve fund categories, almost all of which are regarded either as safe stand-alone investments or potentially stabilizing portfolio hedges, suffered that ignoble fate. I eliminated the two municipal bond groups, because these are before-tax results. I present below the remaining 10 categories along with their cumulative after-inflation losses. (Again, the period is from April 2009 through March 2024.)

| Fund Category | Cumulative Real Return (%) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Commodity Focused | -34.2 | Portfolio Hedge |

| Commodity Broad Basket | -30.4 | Portfolio Hedge |

| Equity Precious Metals | -29.4 | Portfolio Hedge |

| Systematic Trend | -28.5 | Portfolio Hedge |

| Short Government | -19.1 | Safety |

| Intermediate Government | -15.1 | Safety |

| Ultrashort Bond | -12.5 | Safety |

| Global Bond | -7.0 | Portfolio Hedge/Safety |

| Long Government | -6.7 | Safety |

| Short-Term Bond | -2.1 | Safety |

What Happened?

The short version of a longer story is that low-volatility funds have been defeated by low interest rates. In spring 2009, 10-year Treasury bonds yielded 3% and Treasury bills almost nothing. From those levels, fixed-income investments could not possibly record strong after-inflation returns, unless deflation arrived. It did not, and so therefore they did not.

Alternative investments have also been doomed by low interest rates. By and large, their strategies consist of 1) trades that are 2) supplemented by income received from their cash collateral. The former are only as large as a portfolio’s manager’s ongoing brilliance—meaning that they usually are not large at all, as ongoing brilliance is in short supply. Thus, alternatives generally require relatively high interest rates, particularly for cash, if they are to prosper.

(This explanation, I confess, is an overgeneralization. Then again, managers of alternative funds had 15 years to demonstrate their ability to thrive in a low-rate environment, and they were unable to do so.)

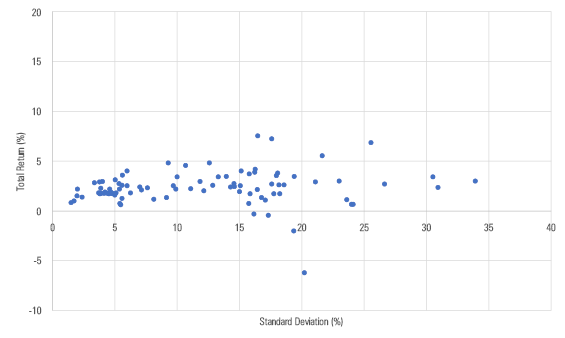

It makes sense that risk and return have been correlated. After all, that is what academic theory predicts. But it is strange that the link between risk and return has been so overwhelmingly positive. The relationship between the two factors is rarely so powerful. Consider, for example, the results from the previous 15 years: Risk and return were only loosely correlated.

The Previous Years

Conclusion

This column should not be read as a criticism of low-risk investments. They aren’t required for younger investors, who need not worry about redeeming their funds at the wrong time (at least, if they are sensible), but they are critical for retirees who are withdrawing their assets. Ballast prevents them from entering a bear market spiral in which they spend ever-larger percentages of their portfolio to realize the same amount of money. Do that for long, and you are in real trouble.

It is, however, a reminder that investment lunches are usually not free. Retreating to bonds, cash, and investment alternatives was psychologically comforting after the 2008 global financial crisis. At that time, for example, target-date families that had relatively high equity stakes were publicly attacked for (allegedly) endangering their funds’ shareholders. Well, yes, those funds were more volatile than their peers. But what feels good is not necessarily what is right. As a rule, competitive gains do not occur without accompanying pain.

That’s a message worth remembering when investment vendors respond to a stock downturn by selling safety. They always do.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)