4 Reasons the Economy Has Been Resilient to Higher Interest Rates

And why we don’t expect that resilience to last forever.

The Fed’s largest and fastest rate-hike cycle in 40 years—a 5.25% fed-funds rate increase between March 2022 and July 2023—was widely expected to generate a recession in 2023. Yet, real gross domestic product growth defied expectations by accelerating to 2.5% in 2023 from 1.9% in 2022.

So why has the economy been so resilient to these higher interest rates?

We attribute it to four key factors:

- Households accumulated excess savings during the pandemic and businesses boosted cash holdings, which are now being spent.

- Many borrowers are locked into low rates, such as mortgages and corporate bonds, for which the interest burden remains low.

- Risky asset prices have held firm, meaning that risky premia have compressed.

- The reduction of risky shadow banking activities (activities outside the traditional banking sector) has rendered the financial system less vulnerable to shocks.

It’s worth noting that the first two factors are purely temporary and the third factor is partly temporary. Therefore, we maintain that aggressive Fed rate cuts are still needed in the next few years to avoid a recession.

We explain how these factors have contributed to the resilience of the economy and where we expect them to go from here.

Households Funneled Excess Savings Into Cash—but That’s Being Spent Down

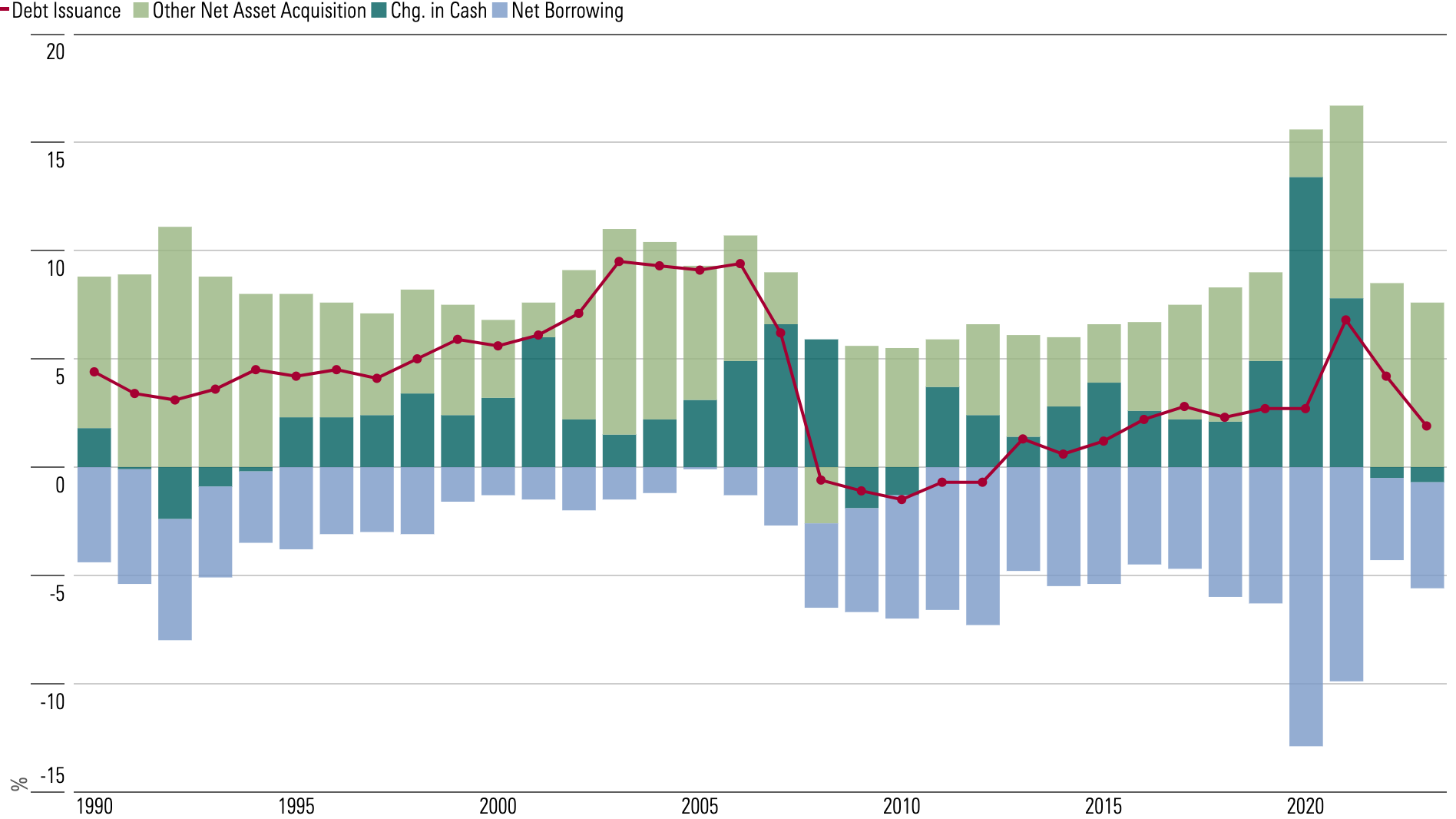

Pandemic fiscal support and restrained spending caused household savings and net lending to spike in 2020 and 2021.

People funneled much of their excess savings into cash: Household cash holdings (including deposits and money market mutual funds) rose to 77% of GDP at the end of 2021 from 61% at the end of 2019. By the end of 2023, the rate had receded to an estimated 66% of GDP as these excess savings were spent down.

Because households’ accumulation of cashlike assets increased even more than the jump in net lending, net issuance of debt increased in 2021 and 2022. That is, though households did use their excess savings to pay down credit cards and other debt (at least at first), this was more than offset by the frenzy of home buying and cash-out refinancing.

Still, debt issuance remained far below levels in the mid-2000s.

Debt Issuance Drivers for Household Sector

Mortgage Interest Burden Will Rise Steadily if Rates Don’t Fall

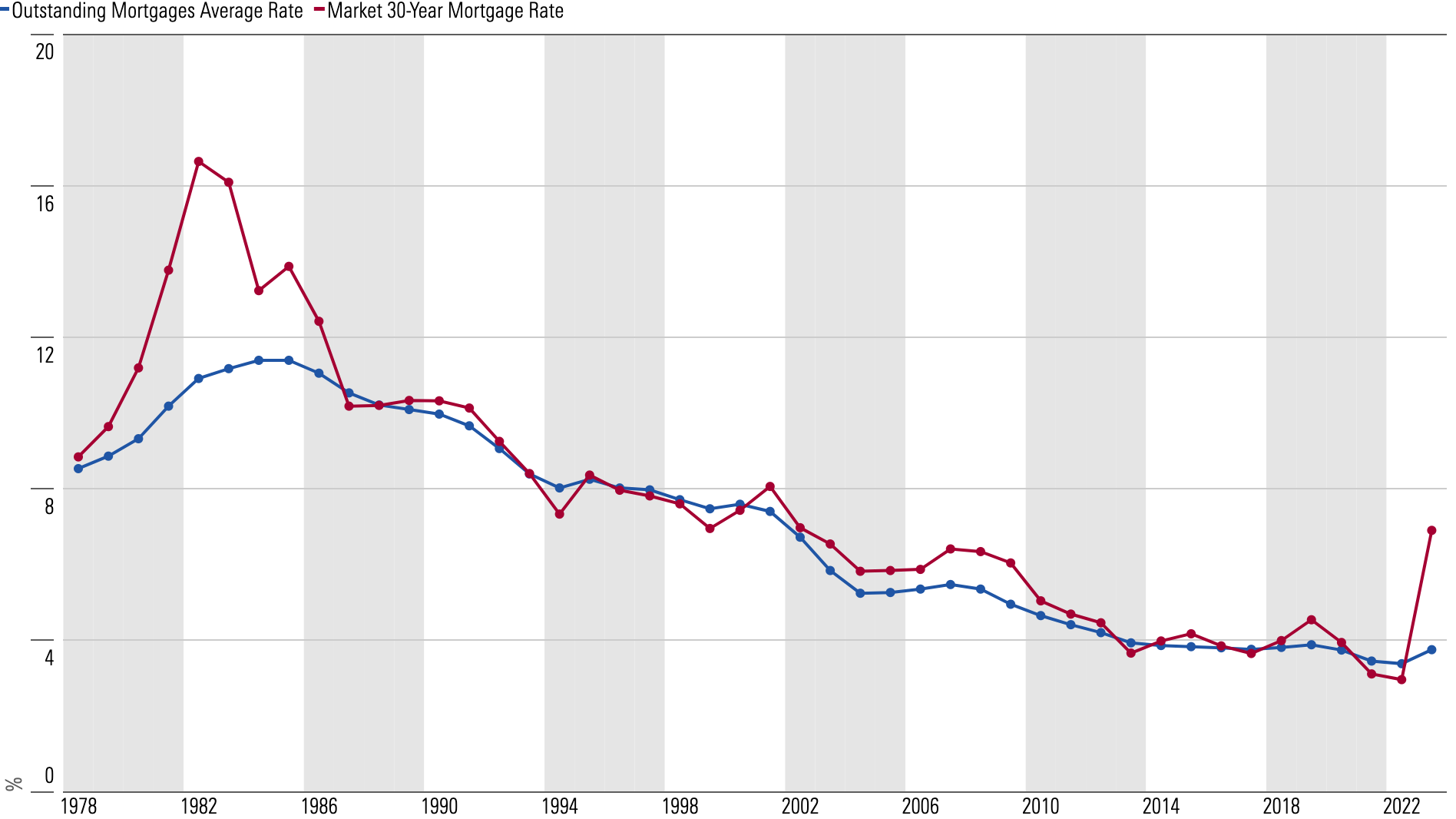

Households’ average interest rates on debt outstanding in 2023 were roughly in line with prepandemic levels. Most household debt consists of fixed-rate mortgages, which are protected against higher interest rates—so even though market mortgage rates and auto loan rates were substantially higher in 2023 than they were before the pandemic, the rate the average borrower is paying is only increasing gradually.

Mortgage Interest Rates: Outstanding Versus Market Rate

In the category of nonmortgage securities, maturities tend to be much shorter, and debt (such as credit cards) is more frequently at a floating rate—meaning average interest rates have adjusted more quickly. Most nonmortgage debt should be rolled over to market rates within the next five years.

That said, nationwide home prices look overvalued if interest rates do not recede. If interest rates do fall, most of this overvaluation should disappear; if they remain high, we think a slow decline in real home prices is more likely than a crash.

On the business side, the soaring of interest rates past prepandemic levels puts their financial health in jeopardy. Many businesses increased their leverage over the past decade, but the interest burden was easily manageable as rates stayed low.

Large public corporations who have fixed-rate debt with distant maturities will be locked into their rates for many years. But commercial real estate looks more vulnerable to distress: This debt carries much shorter maturities, and commercial property prices are likely to see further declines if interest rates remain high.

Risk Premia Have Compressed

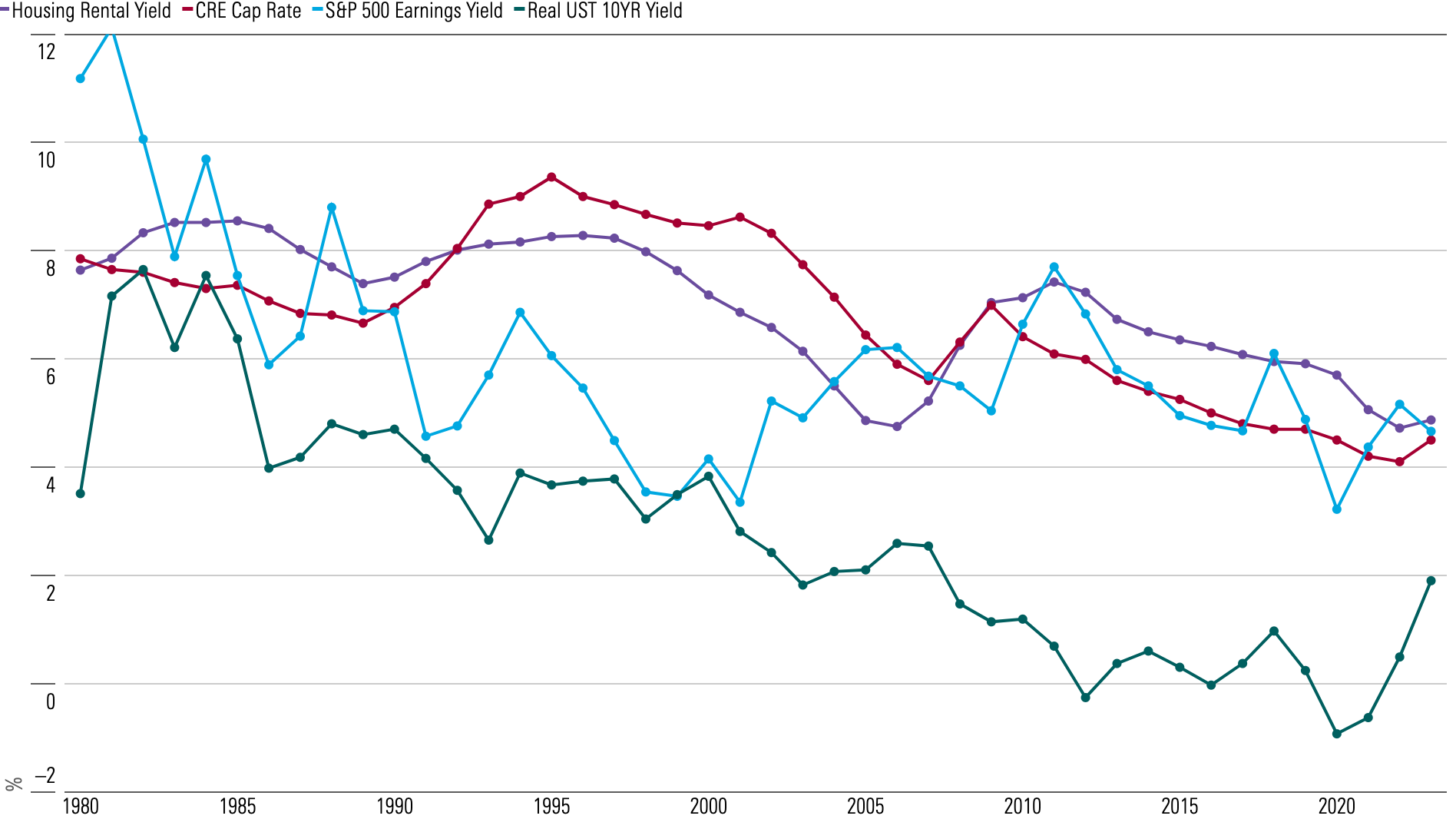

In theory, risky asset prices should decline in response to higher real interest rates.

But that largely hasn’t been the case in this hiking cycle, such as for housing, commercial property, and equities.

- Housing: As discussed above, most mortgages offer a fixed rate, so while new issuances come at a higher rate, the overall market will take longer to reflect these higher rates.

- Commercial property: Commercial real estate poses the largest financial risk in the business sector within the next two to three years if interest rates don’t fall. Because maturities are shorter for commercial real estate than for corporate bonds, their interest burden will rise faster. If interest rates remain high, the only feasible way that cap rate spreads (the commercial real estate cap rate versus the real 10-year Treasury yield) can normalize is a large decrease in property values—which would require a shocking 40% versus 2023 average levels.

- Equities: Valuations in the equity market don’t seem to have been negatively affected by higher interest rates in aggregate. We see that the spread between equity earnings yield and the real 10-year Treasury yield has compressed to about 2%, versus a 2019 level of 4.6%. Still, there is some risk of a reversion to the spread we saw in the 2010s, which would be threatening to equity prices if the real interest rate remains high.

In this chart, we show that income yields on various risky assets have been broadly stable and commensurate with asset prices.

Yields on Real Assets Versus Real 10-Year Treasury Yield

The chart shows that spreads versus the real 10-year Treasury yield have compressed, signifying falling risk premia across the board. Credit spreads have responded more to higher rates but are still on the low side compared with historical averages.

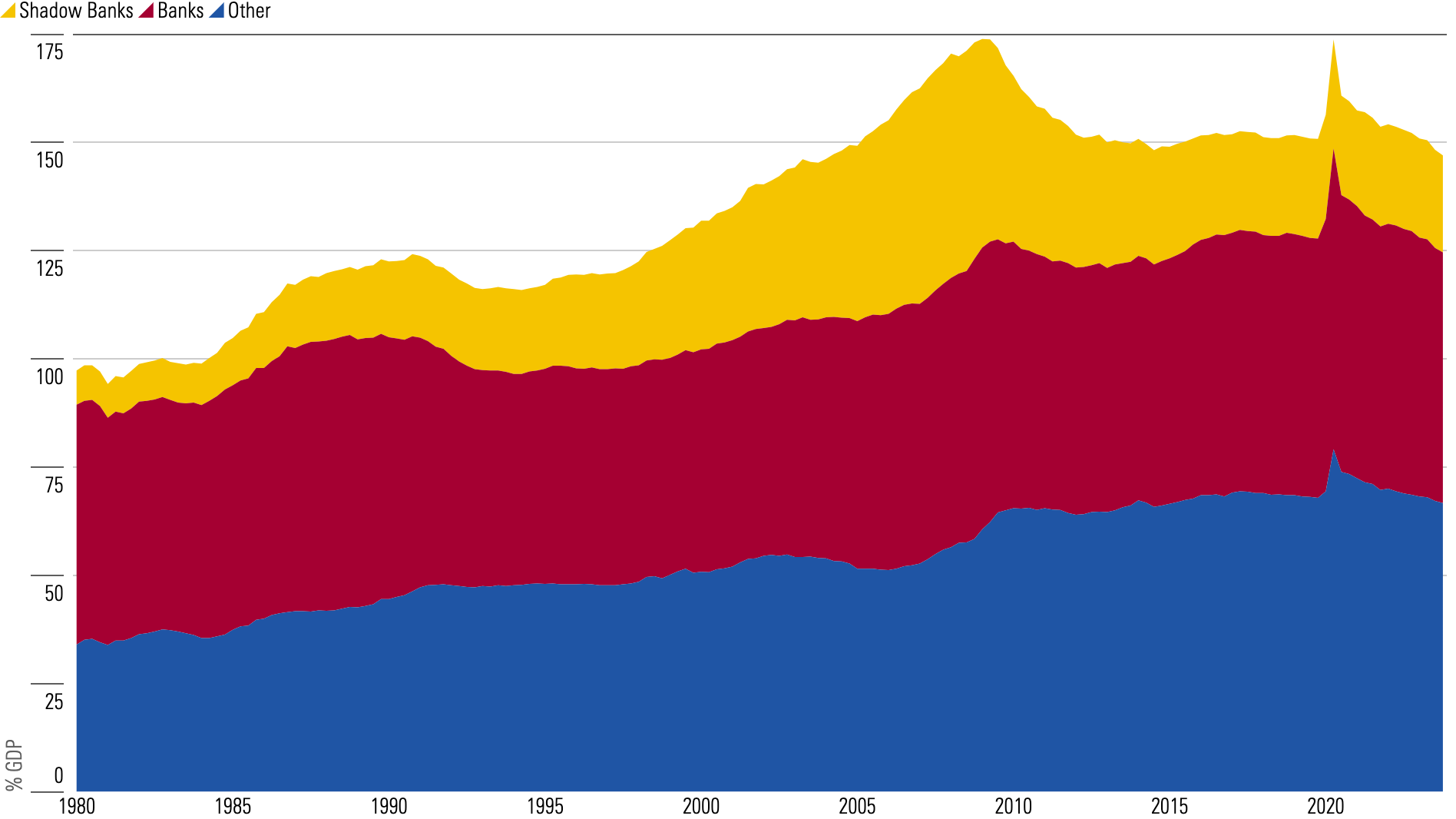

The Shadow Banking Threat Is Mostly Dormant

Shadow banking credit describes lending from nonbank entities that engage in major risk transformation. The growth of shadow banking credit to the private nonfinancial sector—to 51% of GDP in 2007 from 30% in 2000—was a key reason the financial system imploded in 2008.

As the chart below shows, shadow banking credit has since gone back down to 22% of GDP as of 2023—which meant the financial system was less vulnerable to shocks like the interest-rate increase.

Thus, not only has private sector leverage diminished compared with the mid-2000s but also the riskiest financial intermediaries have declined the most.

For this reason, the US financial system is in solid shape—except for the looming monetary tightening.

What Comes Next for Interest Rates?

We still think the Fed will have to cut interest rates aggressively over 2024 and 2025.

We project the fed-funds rate to fall from the 5.25%-5.50% target range (as of April 2024) to 1.75%-2.00% by the second half of 2026. Likewise, the 10-year Treasury yield will fall from 4.60% as of April 2024 to our long-run expectation of 2.75% in 2026 and later years. Essentially, we’re expecting interest rates to return to their approximate averages in the three years before the pandemic.

But what happens if the Fed cuts very little over the next one to two years, as some forecasters expect and as markets had priced in not long ago?

Private sector finances are not structured to weather a permanent rise in interest rates compared with prepandemic levels. Balance sheets are too large and asset prices too high to be compatible with a new normal of higher rates. While these vulnerabilities haven’t manifested to a great degree yet, they will eventually if interest rates remain high.

In other words, the lion’s share of the contractionary impact of Fed rate hikes has yet to play out.

Total US Private Nonfinancial Debt by Holder

Thus, if the Fed fails to move nimbly to reduce rates as we expect, a sharp recession is very likely. Ultimately, a recession would bring interest rates swiftly down to our forecasts, or a bit lower in the short run.

This article was compiled by Emelia Fredlick.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XF7WENSYN5BFBFLPPFH7BJYUHE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HBAEAVIJHFEBTPMEK2UMVQ3NFQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)